If you are a foodie, chances are you’ve packed your own picnic for a long haul flight and wondered why food in the sky is usually so mediocre. Perhaps there is some hope now that so many chefs are getting involved with inflight meals. But it wasn’t always so mediocre. Richard Foss‘ Food in the Air and Space: the Surprising History of Food and Drink in the Skies (Rowman & Littlefield 2015) explores the fascinating history of culinary fare off the earth, the adventurers, the mechanics of in air cooking and serving, and the characters who pursued good food and drink in the air. Reading it, you might wish we were back in the time of dirigibles and hot air balloons rather than supersonic transport.

The first chapter includes the description of a wonderful stove that heated food without a gas flame – which certainly would have destroyed any flight. In September 1936, Charles Green captained a record breaking nonstop flight from France to Germany with a special stove that used quicklime, or calcium oxide, which produces heat when combined with water.

The first chapter includes the description of a wonderful stove that heated food without a gas flame – which certainly would have destroyed any flight. In September 1936, Charles Green captained a record breaking nonstop flight from France to Germany with a special stove that used quicklime, or calcium oxide, which produces heat when combined with water.

The balloon traveled overnight, and at dinner that evening there were many puns about the high flavor the food. Nine people dined on forty pounds of ham, beef, and tongue, forty-five pounds of fowl and preserves, forty pounds of sugar, bread and biscuits, and two gallons each of sherry, port, and brandy. They also had hot coffee, thanks to a quicklime coffee maker developed just for the purpose. (p. 2)

Unfortunately, Foss relates, that the ingenious coffee maker was tossed overboard above Belgium, along with the highly explosive quicklime attached to a parachute.

The next development was the Zeppelin, which took flight even further with motorized lighter-than-air flying machines.

The first of the improved designs was named the Bodensee and flew for the first time on August 20, 1919. It could carry twenty-four passengers in a luxurious salon, and unlike every airship previously built, there was a kitchen for creating inflight meals. It wasn’t a particularly fancy, a single oven with two compartments and a stovetop with two electric heaters, but it was the world’s first all-electric kitchen using all-aluminum utensils. (p. 8)

Turns out that the requirements cooking in the air and space pushed innovation and creativity.

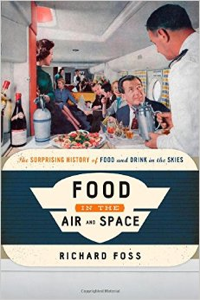

The book is well illustrated with posters, menus, maps, and photographs of “stewardesses” and pilots in their kitchens. If you want more than airplane food, there are several chapters on food in space from Tubes and Cubes (1961-1965) through to the present. There is also a chapter with recipes including SAS’s Fugelbo (Bird’s Nest), an appetizer with Anchovies, pickled beets and capers (p. 196), Tang Pie (p. 199) with Cool Whip, Tang, and condensed milk, and the more tempting Astronaut Fruitcake (p. 197) with pecans, dates, and cherries.

Food in the Air and Space would make a great gift for anyone interested in flight – especially a younger person thinking about a career. It’s more than just a history of the food – it’s a book full of fun facts about the history of aviation – the characters, the stories, and, of course, the cooking.

1 comments on “Richard Foss: Food in the Air & Space”