Away fared they, poets and writers and exotic-wannabes, to “oriental” lands along distant shores fabled in the 19th Century and early 20th centuries… Alas, George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron — generally known as “Lord Byron” fared no farther East than Greece, where he died of fever. As the century progressed, however, and both medicine and travel improved, more personages traveled more successfully and farther afield.

Now, the American University in Cairo Press is offering two additions to its ongoing series on “Travel Writing through the Centuries” — which, of course, include descriptions of food and drink.

In A Nile Anthology (forthcoming), Americans may be surprised to discover Yanks were visiting Egypt, from New York dentist William Jarvie to the better known Florence Nightingale. Many more eminent Europeans appear here, though overall visitors found more about which to rhapsody on Egypt’s millennia of historic artistic and architectural wonders.

In A Nile Anthology (forthcoming), Americans may be surprised to discover Yanks were visiting Egypt, from New York dentist William Jarvie to the better known Florence Nightingale. Many more eminent Europeans appear here, though overall visitors found more about which to rhapsody on Egypt’s millennia of historic artistic and architectural wonders.

Nevertheless, the alluring, French speaking Princess Marta Bibescu of Romania took time in her French-language memoirs Eight Paradises to share a memory of dining in the Karnak temple complex in Thebes, Egypt. Dinner is so exotic that it starts not with food but with “the perfume of mimosa.” Wait staff appear dreamily like “black shadows against the skies” like “jinn out of the air.” She eats strawberries just a few feet from “the eighth wonder of the world” (Karnak) and finishes with coffee cups full of “the moon on a silver salver” (pp. 80-81).

So much for 19th Century food fare in “Egypt Land.”

In An Istanbul Anthology (forthcoming), however, food figures fare more frequently. Americans will find more Yanks of greater fame, including writers from Herman Melville to Mark Twain to Ernest Hemingway.

In An Istanbul Anthology (forthcoming), however, food figures fare more frequently. Americans will find more Yanks of greater fame, including writers from Herman Melville to Mark Twain to Ernest Hemingway.

Georgina Max Mueller (wife of German philosopher Max Mueller) mentions a picnic in the Belgrade Forest (pp. 26-27). Italian writer Edmondo de Amicis talks of the fish and grand bazaars (pp. 92-93: Mark Twain can only complain of the smells of the Grand Bazaar, pp. 93-94). Harrison Griswold Dwight, an American who later directed the Frick Museum in New York, describes the spice and fruit bazaars, which “fill the air with the aroma of the East” (pp. 95-96), as well as the making and eating of an iftar meal — though, as he confesses, “any Turkish dinner is colossal” (pp. 101-103). The French writer Theopile Gautier complains that in 1852 nothing could be “plainer” than a Turkish coffeehouse (p. 110) — though of course he did not live to see branding of Starbucks land in Turkey either.

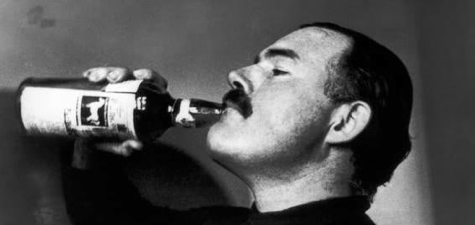

Speaking of coffee and plainness, perhaps Ernest Hemingway had been dipping too deeply into other drink before his first Turkish coffee, because he came up with a term for the latter (“deusico“) that appears nowhere else. This “poisonous, stomach rotting drink,” he claims, has a “greater kick than absinthe” (pp. 113-114). (The recipe in the Hemingway Cookbook for “deusico” is a mild affair, in contrast.)