Chefs and their craft are apt to be put under the gaze of the Structuralist, and Post-Structuralist critics. Each of these theories of criticism when applied to Art, Literature, or even the written work of chefs, reveals different — competing — things about the same text.

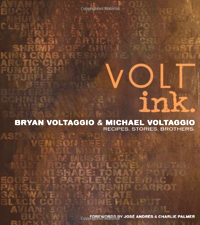

What, then, is the best way to approach Bryan and Michael Voltaggio‘s VOLT ink (Olive Press 2011), by brother chefs Michael Voltaggio and Bryan Voltaggio?

Certainly, to ignore the background, personal relationships and family these two chefs share would be ludicrous, and yet they do not dwell on it as much as they could have. There are no pictures of Mom or Dad or other family members. There is little about the details of the food they grew up with — the TV shows they watched or books they read.

When these two write about families, it is about flavor families — how Avian (Squab, Quail, Chicken) or Buckwheat (Buckwheat Flour, Sorrel, Buckwheat Groat, Rhubarb) give them ideas — that have them to compete before us. They force us to be Structuralist. It’s as if their new cookbook were saying, “Think about the food: that is what we are.” This gives the book inner tension between their own Structuralist approach and the Post-Structuralist urge in readers to want to know the authors more.

They invite comparison in Food: readers want to tease apart their psyches. Here are two brothers, both chefs. How did nurture affect nature? How did the role of their mentors help form their own signature styles?

The Voltaggio Brothers answer in restaurant recipes, constructed like a competition between two chefs, but really a challenge to see whether readers can tell them apart.

The Voltaggio Brothers answer in restaurant recipes, constructed like a competition between two chefs, but really a challenge to see whether readers can tell them apart.

Chefs Michael and Bryan have both worked for Charlie Palmer, who penned a forward. Michael worked at Dry Creek Kitchen, and Bryan at Charlie Palmer Steak. They have competed against each other on Top Chef. Jose Andres knows both chefs as well, since Bryan used to work nearby in Washington DC, while Michael worked for him at The Bazaar by Jose Andres in LA:

No one knows you better, and no matter how different you grow up to be or how much distance separates you, your sibling understands you like no one else does. Unlike most brothers, the connection between Bryan and Michael has the added layer of their connection through the kitchen. Both of them are amazing and talented cooks, among the best I know.

Is this about understanding or competition – or both?

Figuring that out is plenty of fun.

Bryan’s Whole Roasted Squab, Brussels Sprouts, Chanterelle Mushrooms, Salsify Variations (pp. 11-15) is a sous vide preparation of his one of his “favorite birds” as well as circulating water bath for the Brussels Sprouts and salsify — the last two would make incredible additions to Thanksgiving, if you could cook sous vide at home.

Michael’s dish is Chocolate Tea-Roasted Quail, Banana Polenta, Truffle Bolognese (pp. 16-19), which also uses a thermal immersion circulator. He makes an amazing Arugula –Tarragon Gelee that looks like squares of banana leaf.

A chapter entitled “Grain: Corn Rye Wheat” has an odd assortment of recipes. Michael offers Pulpo alla Gallaga, Buttered Popcorn, Piquillo Paper (pp. 146-148) with luscious octopus tentacles arching over a buttery puree of popcorn and cream, and dehydrated Piquillo pepper puree in a lovely photo by Ed Anderson. Bryan’s dish is Rye Cavatelli, Parmigiano Broth, Broccoli Rabe, Country Ham (pp. 150-151) is an inspired dish using a local ingredient – in this case, shaved Virginia ham – to enhance an Italian dish. Michael’s second recipe is for Bacon Knot Challah (p. 53), that seems delicious (though totally un-Kosher) but also quite simple compared to the other recipes in the book – it isn’t a restaurant dish, but a recipe for a bread to use in French Toast – and yet, there isn’t any plated French Toast recipe to follow it. Bryan finishes off the chapter with another pasta dish, Goat Cheese and Ash Ravioli, Mushrooms, Parsley Root (pp. 154-157). He uses the vegetable ash that covers the goat cheese in the pasta, rather then squid ink. The ravioli themselves are a play on the cheese inside.

This is a striking book with beautiful photography of painterly plates and the hands of chefs putting them together. It may prove difficult book to use in a home kitchen. Regardless, it is rich in ideas and reveal the trends, inspiration, and direction of two young, gifted American chefs.

Still, Super Chef wonders: is there another book to follow that will fill in the gaps or decipher the code of a secret fraternal language that lies beneath the recipes?