Why does New York City seem foreign to many Americans?

Is it because New York City is a “world city,” as Tony Judt calls it (in his final book, The Memory Chalet)? A place not just full of foreigners but about which people track in faraway lands?

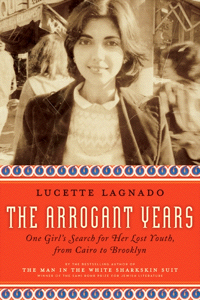

The Arrogant Years defies (or augments) this definition, for thoroughly this is a book about a first generation in New York City, more specifically in Bensonhurst — an area so insular that to its residents Manhattan is “the City” (p. 6).

This second memoir by journalist Lucette Lagnado is ostensibly about her mother, as the first about her father. Lagnado, an investigative reporter for The Wall Street Journal, was born in Cairo, Egypt. Her book stretches out to faraway Egypt, back to a time before Nasser and the 1952 Revolution, before Egypt’s last King Fuad II to the days of King Farouk — the days of her mother’s childhood. It traces the mother-daughter relationships down three generations, hardships in Cairo, and hardships in America.

Whether intentional or not, The Arrogant Years studies many aspects of life. First, it shows the impact of major political events on personal lives — sharply defined for the author’s parents, both of whom already lived on the margins of their society. It provides a study of the culture of religion, specifically Sephardic Judaism. Interestingly, at no time does the author address her own religious beliefs seriously. If anything, she seems inclined to a Darwinian outlook on the universe (pp. 119-120), ready to break out from the women’s section of her synagogue (pp. 1-18) and embrace a working world liberated by the Feminist Movement of the 1970s (pp. 220, 257, 289).

Whether intentional or not, The Arrogant Years studies many aspects of life. First, it shows the impact of major political events on personal lives — sharply defined for the author’s parents, both of whom already lived on the margins of their society. It provides a study of the culture of religion, specifically Sephardic Judaism. Interestingly, at no time does the author address her own religious beliefs seriously. If anything, she seems inclined to a Darwinian outlook on the universe (pp. 119-120), ready to break out from the women’s section of her synagogue (pp. 1-18) and embrace a working world liberated by the Feminist Movement of the 1970s (pp. 220, 257, 289).

This book is clearly memoir, not biography or chronicle of the times. It focuses on the line of women: grandmother Alexandra, mother Edith, and daughter Lucette. In fact, it is a tale of growing up and learning — often too late to appreciate what once was or to thank those who provided. The title — a quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald — implies introspection. By the book’s end, there are only leads for this journalist to follow, delivering her in front of items made precious by hands that once may have touched them — even such tactile sense left not totally certain:

I felt as if I were touching my mother’s hand, exactly as I had as a little girl, when she would not let me go, she would not let me go (p. 383).

Food makes its presence felt most vividly in fasting — out of dire straits as often as by choice. There are no recipes and few specific references. But food or fasting appears in important moments, such as days that the 1964 New York World’s Fair, when the family would spend the day at the Egyptian Pavilion, encamped in the Crocofile Cafe and eating locomadis (p. 162).

Some sections will special meaning to anyone new to America, to our most American of birds (turkey), and Thanksgiving:

Edith [my mother] tried to satisfy my longing for “du turkey.” At our local Key Food, the small supermarket on Twentieth Avenue, Edith had found a cooked kosher turkey breast in the frozen foods section. It came in a tinfoil container and had an enticing image of a brown turkey on its wrapping. My mother plunked down an exorbitant amount for it and then tried to follow the elaborate directions on how to prepare it. Yet no matter how carefully she cooked it — and how excited I was at the prospect of eating turkey — the final product was inedible. Yet my mother continued to buy it year after year, eager to have me enjoy a semblance of this holiday that filled me with so much longing. (pp. 291-292)

Despite a frequent tone of childlike wonder, this is an autobiography is which the narrator wrestles with the past. At times, it cannot help being self-conscious. In truth, it takes a brave heart to plumb the depths of self-doubt that nag this author — and richly rewards the daring reader.

Somewhere in the background, one almost hears the beseeching of Chorus:

Who prologue-like your humble patience pray,

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play.

(Henry V, Prologue)

(Please click here to read a longer excerpt about Thanksgiving at the home of an American family.)

Other reviews:

NPR

New York Times

San Francisco Chronicle

Boston Globe

Washington Post

Jewish Week

(Photo of Lucette Lagnado from Suma de Letras)

1 comments on “The Arrogant Years: Lucette Lagnado”