If Italy’s gift to the world is Pizza (among other things), then Lebanon’s gift is man’oushe. There are plenty of cookbooks only on pizza – and thankfully, there is now a cookbook devoted to man’oushe.

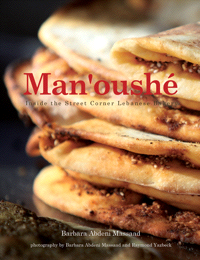

Barbara Abdeni Massad’ Man’oushe: Inside the Lebanese Street Corner Bakery (Interlink 2014) will expand your mind and palate when it comes to flatbread. A crisp man’oushe topped with fragrant wild thyme za’tar can take on any Neapolitan pie.

So, what’s man’oushe?

The man’oushe is the quintessential Lebanese breakfast. Named for the Arabic word na’sh, which refers to the way the fingertips of the baker “engrave” the dough, the man’oushe is indeed engraved upon our collective memories as Lebanese. The smell of man’oushe bi-za’tar in the morning catapults a Lebanese person back in time to a lively childhood birthday party, breakfast on the go with classmates before an exam, or a cozy morning spent tete-a-tete with a loved one. (p. 7)

And even if you aren’t Lebanese, eating a stack of mana’ishe (plural of man’oushe) will make you wistful for Beirut.

Man’oushe starts with Barbara’s story, her childhood in Lebanon and then later in the US, her parents’ restaurant, her return to Lebanon, and finally her apprenticeship in French and Lebanese restaurants. Her quest is this book on man’oushe – including glorious photographs (by Barbara and Raymond Yazbeck) of bakers, their customers, the raw ingredients, and the multitude of different breads for sale. Barbara spends time on ingredients, kitchen tools, and cooking methods including baking on a stone or a cast iron pan. Traditionally, the Lebanese use a saj, a kind of convex metal disc for flat breads. There are recipes for man’oushe dough as well as Arabic Bread and Paper-Thin Bread (pp. 42-9).

Man’oushe starts with Barbara’s story, her childhood in Lebanon and then later in the US, her parents’ restaurant, her return to Lebanon, and finally her apprenticeship in French and Lebanese restaurants. Her quest is this book on man’oushe – including glorious photographs (by Barbara and Raymond Yazbeck) of bakers, their customers, the raw ingredients, and the multitude of different breads for sale. Barbara spends time on ingredients, kitchen tools, and cooking methods including baking on a stone or a cast iron pan. Traditionally, the Lebanese use a saj, a kind of convex metal disc for flat breads. There are recipes for man’oushe dough as well as Arabic Bread and Paper-Thin Bread (pp. 42-9).

Perhaps the most important ingredient in the book is za’tar, a wild thyme, sesame seed and sumac spice mixture that is sprinkled with olive oil and baked on man’oushe or eaten with olive oil on practically any kind of bread. It’s easy to find it in Middle Eastern stores – but Barbara provides a recipe (p. 54) with a wonderful photograph of an older woman collecting wild thyme and another plucking off the leaves. There are recipes for Man’oushe biz-za’tar (p. 57) – the bubbly pie that is fragrant with thyme and toasted sesame with a photo of Barbara’s daughter Hannah hungrily gobbling up a crisp slice, or the slightly more complex version topped with pink pickled turnips, tomatoes and mint with a photo of her son Albert eating breakfast man’oushe.

If you are looking for more – there are chapters on Cheese Pies including a Strained Yogurt Pie (p. 85) or Labneh, which goes by the name “Greek Yogurt” these days. That’s followed by a whole chapter on Dried Yogurt and Bulgar Pies, and then various chapters on Meat, Vegetable, Chicken and Armenian Sausage Pies. If you are familiar with Turkish Lahmacun, then you’ll find the Armenian Meat Pie (p. 157) quite close.

Lastly, there is a chapter on Sweet Pies, including a Chocolate Pie (p. 184), a Helawa Pie (p. 187), and a Molasses and Sesame Paste Pie (p. 189).

With the Middle East – especially Syria and now Lebanon – embroiled in war, it is reassuring to find a book that includes such nostalgic and optimistic photographs of the people and food of the region. Buy this book for the stunning photos, but then try your hand at making man’oushe – it is well worth the trouble.